Experimental Freud-Lacan: Beyond the Folklore

By R. T. Groome

(Pre-Print 2000/ Revision 2011,12, 13)

I – Things Never Before Looked At

Let us begin with a seemingly obvious assumption made by M. Foucault: that the Birth of the Clinic began in the 19th century when a few bodies were opened up to reveal the invisible cause of illness. If true, then this historical moment not only transgressed the ancient Aristotlean prohibition that there can be no science of the individual, but replaced the previous method of natural philosophy that had classified diseases into species like flowers. Now a scientific anatomico-pathological method not only opens the body up and maps it out flat on the plane, but in doing so reveals its 'lesions': those local anomalies of the represented body that are disruptive to its functioning. If this is true, then by the 19th century the symptom is no longer – or not simply – the visible effect, but the disease itself is no longer a hidden cause: it becomes accessible to the language of observation and a whole host of instrumental procedures – surgery, microscopic analysis, experimental modeling, etc. – and sciences – neurology, chemistry, biology, and genetic.

That this common historical account of the Birth of the Clinic may be reformulated in various ways or even refuted to suit the researcher's favorite epistemology or ontology, will not detain us – leaving each to develop their ideas as they can.

My intervention lies elsewhere: in the structural argument and the construction of the object Freud discovered in one of the last flowers of modern medicine – psychoanalysis. If our approach is sound, then the story of the invisibility of the diseased body that was supposedly revealed in the modern medical clinic is not a closed chapter. This invisibility must be read and written in all its traces, effacing, and assimilations, before pathologizing it into forms of disease and illness. At least this is what we aim to show.

Beyond The Psychoanalytic Folklore

Before beginning, however, a caution should be made with regard to a position that threatens to derail our argument before it even begins: I am not making the analogy that invisible cause is to visible law of disease as spiritual theory (psychosomatics, homeopathic, mindfulness, etc.) is to positive science (neurology, biology, genetics, etc.). It is not a question of a mind-body separation: it is not a question of opposing a psychology of the soul to a psychiatry of the brain. On the contrary, I will show that there is a reading and writing of the body that can be constructed in a way such that any perceived invisibility – an effacing or trace – is not due to the interventions of a mysterious force – spirit, soul, or subconscious mind – but a reading and writing effect. It is this other body of a text that requires a construction.

Where our intervention differs from both past and most current Freudo-Lacanian accounts is that we do not leave the construction of this other body to folklore: an inertia of legends and tall tales, both scholarly and popular, recounted through literary, philosophical, and therapeutic examples[1]. This is not to say we discount this early style of working in psychoanalysis. Indeed, many important questions have been raised using a supple logic of intuition to get at serious structural problems. But what is evident, at least at this late date, is that left to such intuitive and folkloric interrogations there is no effective way to arrive at a response beyond an appeal to charm and the consensus of others. Said otherwise, just because there is a nice hammer to bash and critique things does not mean there are the nails to effectively construct something. Beyond the folklore, what is required today is to supply the nails so that the arduous work of a construction can not only begin, but be achieved – beyond the charm and demand for consensus that too often pass off as Freudo-Lacanian 'theory' and 'practice'.

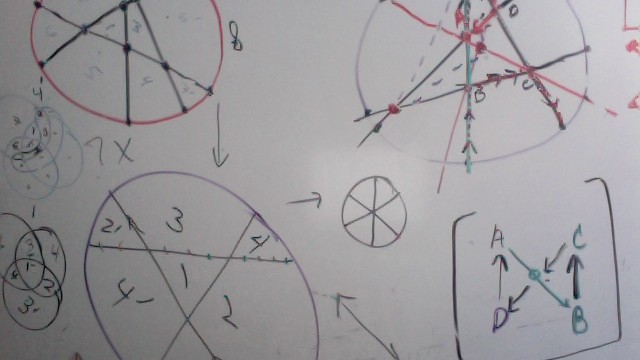

The Structural Problem: From Semiotic Triangle To Projective Diagrams of Signifiers

To begin with, any historico-philosophical attempt to account for a medical origin is forced to start, either implicitly or explicitly, with something like a medical semiotics in which any possible observation is arranged according to the infamous semiotic triangle of signs (continued in Pre-Print Manual scheduled for 2014 publication by R.T. Groome @ PLACE )

[1] - To call a tiger a tiger, even if it is a paper tiger, this author prefers to develop his literary fantasies in a more direct manner – in the illustration and writing of books for children. See http://www.blurb.com/b/4296593-comparing-angels-and-other-creatures